By Yahuza Bawage, Abdullahi Sidi, Sakina Ahmed, Gloria Abutu, Abdulaziz Ibrahim, Ummulkulchumi Hammanadama, Aminu Adamu Ahmed, Acheli Obidah, Saddam Mohammed, Abubakar Ibrahim, and Vangawa Bolgent

In May 2024, the heat in Adamawa State stopped being a seasonal inconvenience and became a silent killer. By midday, the air in Yola felt suffocating. Roads shimmered. Fans blew warm air. Buckets of water left indoors became tepid within minutes. Then people began to collapse.

Across Yola metropolis and nearby communities, residents told similar stories. A commercial driver slumped over his steering wheel along a busy route. An elderly woman was found lifeless in a poorly ventilated room. Market traders fainted in clusters under zinc roofs. Families whispered about sudden deaths, but no official numbers followed.

Community estimates put the figure at around 200 deaths during the peak heat period. Yet, more than a year later, Adamawa State has no public record of heat related mortality from that period. There was no emergency declaration. No official investigation. No consolidated report explaining what happened.

What unfolded in Adamawa was not only a climate emergency. It was an institutional failure that exposed how extreme heat, weak data systems, fragile infrastructure, and poor public awareness can combine to kill quietly.

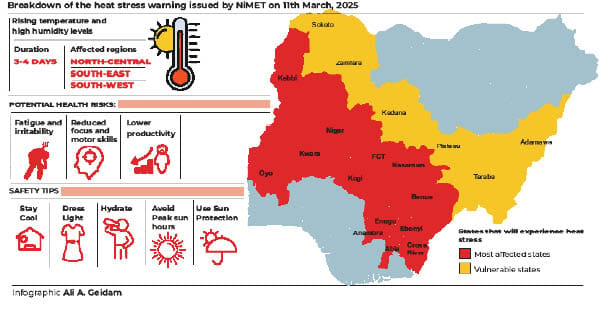

Nigeria experienced one of its hottest years on record in 2024. According to meteorological data, temperatures in several northern states repeatedly crossed 40 degrees Celsius between March and May. Yola, already one of Nigeria’s hottest cities, endured prolonged heat stress during those months. The Nigerian Meteorological Agency issued warnings about severe heat stress across the North East, urging residents to avoid outdoor activities during peak hours and to hydrate frequently.

Those warnings rarely reached the people most at risk.

At the Modibbo Adama University Teaching Hospital and the State Specialist Hospital in Yola, doctors say admissions surged during the hottest weeks. Patients arrived confused, dehydrated, and sometimes unconscious. Many did not survive.

“Heatstroke is the most dangerous form of heat illness,” a senior clinician at MAUTH told HumAngle. “But it is often mistaken for malaria or exhaustion. By the time families realise what is happening, the organs have already been damaged.”

Heatstroke occurs when the body loses its ability to regulate temperature. Once the core temperature rises above 40 degrees Celsius, the brain, kidneys, and heart begin to fail. Without rapid cooling and fluids, death can occur within hours.

Despite this, heatstroke is rarely diagnosed or recorded as a cause of death in Adamawa.

Dr Damba Dakarewa Kuinke, former State Epidemiologist at the Adamawa Ministry of Health, confirmed that no official data exists on heat related deaths during the 2024 heatwave.

“The heat was extremely high and could cause death,” he said. “But officially, our public health emergency unit did not receive reports of deaths due to excessive heat.”

Dr Kuinke explained that the state surveillance system is designed primarily to detect infectious disease outbreaks like cholera, measles, and Lassa fever. Heat related illness often falls through the cracks because it presents with symptoms that mimic other conditions.

“People come with dizziness, dehydration, confusion,” he said. “These are treated clinically, but they are not always reported as heat cases.”

This gap between lived reality and official records has deadly consequences. If deaths are not counted, they do not trigger policy responses.

A December 2025 survey conducted by journalists and researchers in Adamawa sheds light on what official systems missed. The survey covered 79 residents across Yola North, Yola South, and Girei local government areas, including traders, tricycle drivers, households, and community leaders.

While 96.2 percent of respondents agreed that extreme heat poses a serious health risk, 75.9 percent could not identify key symptoms of heatstroke such as hot dry skin, confusion, or loss of consciousness. More than 73 percent said they had personally collapsed from heat exposure or witnessed a family member collapse between 2024 and 2025.

Those most affected were people whose livelihoods depend on outdoor work. Keke Napep drivers, market traders, food vendors, security guards, and transport workers spend long hours under direct sunlight. Few receive weather alerts. Even fewer receive health guidance tailored to their daily realities.

For many, staying indoors during peak heat hours is not an option. It is a threat to survival.

The danger intensifies when electricity fails.

Nearly 90 percent of survey respondents blamed frequent power outages by the Yola Electricity Distribution Company during peak heat hours between noon and 4 pm for worsening the situation. Without power, fans stop working. Refrigerators fail. Water warms quickly. Medicines lose stability. Hospital wards become ovens.

Doctors and nurses describe fighting heat not just in patients but within health facilities themselves.

Zainab Bamanga, a nurse at the State Specialist Hospital in Yola, said conditions were unbearable before solar power was installed.

“You would see nurses sweating while doing rounds. Patients were uncomfortable and restless,” she said. “Children and maternity wards were the worst.”

Dehydration was common among patients and staff alike.

“When NEPA went off, everywhere became hot again,” she said. “We opened windows and encouraged people to drink water. Relatives used hand fans to cool patients.”

The installation of solar panels improved conditions in the Specialist Hospital, but many primary healthcare centres still struggle with unreliable power and limited cooling capacity.

At PHC facilities in Yola North and Yola South, health workers say heat related illness increases every dry season. Common cases include high blood pressure crises, dehydration, malaria, measles, cholera, and cerebrospinal meningitis, all of which are worsened by extreme heat.

“We treat according to symptoms and advise patients to stay in ventilated places,” a PHC worker in Yola North said. “Severe cases are referred to secondary facilities.”

Some PHC workers receive alerts from NiMet, but there is no structured system for translating forecasts into community action. No standard message. No heat response protocol. No mobilisation plan.

Low cost interventions could make a difference, health workers say. Free oral rehydration salts, IV fluids, functional boreholes, solar powered fans, and cooling spaces for vulnerable groups such as internally displaced persons, prisoners, students, and the elderly.

Most centres rely on improvisation.

The lack of coordination reflects a broader institutional gap. Despite repeated heat warnings, Adamawa State has no Heat Health Action Plan. There is no unified alert system linking NiMet forecasts to public advisories, health facility preparedness, and power prioritisation.

Public education is fragmented and often delivered only in English. In rural and semi urban communities, this limits impact.

“If the government produced simple heat safety information in Hausa and Fulfulde, it would save lives,” Nurse Bamanga said. “Pictures showing symptoms and what to do would help people understand quickly.”

Global data underscores the urgency. According to climate and health research, heat exposure in Nigeria has increased steadily over the past three decades. Studies show that average Nigerians now experience over 30 heatwave days annually, most of them linked to climate change. Heat related mortality has more than doubled since the 1990s, long before the 2024 crisis.

The World Health Organization warns that climate change will cause hundreds of thousands of additional deaths globally each year between 2030 and 2050, with heat stress among the leading drivers.

Adamawa is already living that future.

In markets across Yola, traders describe closing early when the heat becomes unbearable. Drivers talk about dizziness behind the wheel. Mothers speak of children convulsing in overheated rooms. Elderly people faint quietly indoors, sometimes unnoticed until it is too late.

“These deaths are not accidents,” Dr Kuinke said. “They are preventable.”

Prevention requires more than advice. It requires planning, data, and accountability. Experts and frontline workers point to clear steps. A coordinated Heat Health Action Plan. Public education in local languages. Stronger collaboration between NiMet, the Ministries of Health and Environment, primary healthcare agencies, hospitals, and the media. Standard heat protocols in hospitals. Reliable power supply for health facilities. Protection for outdoor and informal sector workers.

Until these measures are taken, heat will continue to kill silently in Adamawa. The bodies will be buried. The records will remain empty.

The next heat season will arrive by late February. The question is not whether temperatures will rise again. It is whether the state will finally count the dead and act before more lives are lost.

This report is produced by the HumAngle Foundation’s Adamawa Strengthening Community Journalism and Advocacy (SCOJA) Fellows. It aims to raise public awareness, inform policymakers, and encourage evidence-based responses to emerging climate and public health risks in the state