By Yahuza Bawage, Abdullahi Sidi, Sakina Ahmed, Gloria Abutu, Abdulaziz Ibrahim, Ummulkulchumi Hammanadama, Aminu Adamu Ahmed, Acheli Obidah, Saddam Mohammed, Abubakar Ibrahim, and Vangawa Bolgent.

In May 2024, Adamawa State faced a terrifying public health crisis with temperatures soaring above 40°C, and as a result of that, about 200 sudden deaths were reported across Yola, the state capital, and surrounding communities.

Even as families mourn their loved ones, the scale of the tragedy points to a systemic failure to protect residents from the growing threat of extreme heat.

Doctors at Modibbo Adama University Teaching Hospital (MAUTH) Yola, and the State Specialist Hospital, Yola, report that admissions increased during the hottest months, but many patients arrive too late.

They, however, added that heatstroke, the deadliest form of heat illness, is often mistaken for malaria, dehydration, fatigue, or even spiritual affliction. And by the time families realise the severity, it is frequently too late to save lives.

A December 2025 survey conducted by a team of journalists, researchers, and advocates in Adamawa who engaged 79 residents – including market traders, Keke-Napep drivers, households and community leaders – in Yola North, Yola South, and Girei local government areas revealed that while 96.2% acknowledged that extreme heat poses a serious risk, 75.9% could not identify the key symptoms of heatstroke, such as hot, dry, red skin or confusion. More than 73% reported personally experiencing, or witnessing a family member suffer, collapse from the heat between 2024 and 2025.

Those whose livelihoods demand prolonged outdoor exposure, traders, drivers, food vendors, security personnel, are the most at risk, yet they are the least likely to receive formal weather alerts or health guidance.

Also, nearly 90% of respondents cited frequent power outages by the Yola Electricity Distribution Company (YEDC) between 12 p.m. and 4 p.m., the peak heat hours, as making the conditions “deadly.” Without electricity, fans and cooling systems fail, water becomes warm, medicines lose stability, and hospital wards become overheated. Doctors admit they sometimes fight the heat not only in their patients, but in the hospital itself.

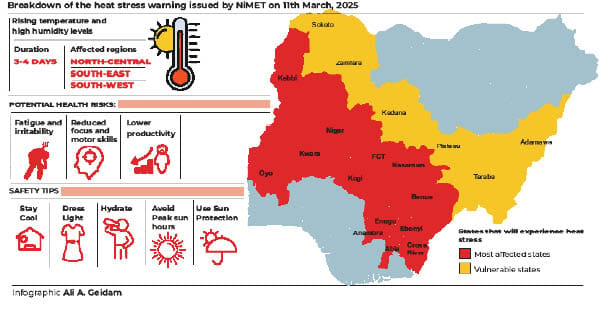

Despite forecasts from the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet), there is no formal system in Adamawa to translate the scientific warnings into protective action.

Experts noted that even though scientific knowledge exists, it does not reach those who need it most due to lack of unified alert strategy, local language guidance, standard messaging for outdoor workers, and there is also no standard hospital protocol for heat surges.

The climate crisis in Adamawa intersects with economic vulnerability, and ordinary residents bear the weight more, especially drivers who are found collapsing mid-route, older people fainting in overheated rooms, mothers cradling children suffering seizures, and market vendors forced to choose between heat exposure and income.

Now, Adamawa urgently needs a coordinated Heat-Health Action Plan, public education in Hausa and Fulfulde, stronger collaboration between NiMet, the State Ministry of Environment, the State Ministry of Health, Primary Healthcare Development Agency, and the Media, hospitals heat protocols, prioritised power supply for health facilities, structured monitoring of heat-related illness, and support for outdoor and informal-sector workers.

Until these coordinated actions are fully taken, preventable deaths will likely continue during peak heat periods.

Adamawa still has time to act. And that is now.

Caveat

This report is produced by the HumAngle Foundation’s Adamawa Strengthening Community Journalism and Advocacy (SCOJA) Fellows. It aims to raise public awareness, inform policymakers, and encourage evidence-based responses to emerging climate and public health risks in the state