Prison Oversight, Organ Donation Ethics, and Consent

By Anidjar & Levine Research and Policy Analysis Team

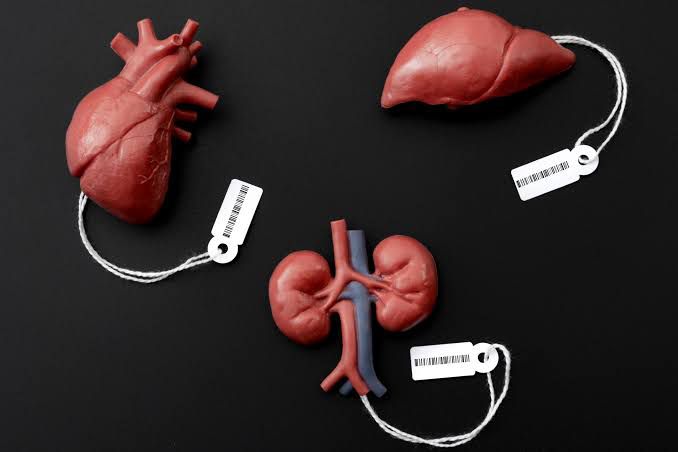

The intersection of prison oversight and organ donation surged into public consciousness through a string of scandals in 2024 and 2025 that exposed deep systemic failures in consent procedures, family notification, and post-mortem handling of incarcerated individuals’ remains. From Alabama’s missing-organs crisis to Harvard Medical School’s body-trafficking scandal, these cases revealed profound breakdowns in protecting bodily autonomy and the dignity of vulnerable populations, both living and deceased.

A crucial clarification is needed at the outset. HBO’s The Alabama Solution is not about organ donation. The documentary, which premiered at Sundance on January 28 2025 and aired on HBO on October 10 2025, exposed violence, deaths, and inhumane conditions inside Alabama’s prisons. Nearly 1,400 inmates died between 2019 and 2024. The title echoed Governor Kay Ivey’s remark that “an Alabama problem deserves an Alabama solution,” made when federal officials threatened intervention. In contrast, the separate issue of organ-donor registry removals was triggered by a July 20 2025 New York Times investigation by Brian M. Rosenthal and Julie Tate documenting premature organ-retrieval attempts from patients showing signs of life. Distinguishing these two stories matters: it reveals how multiple crises—prison oversight failures and unsafe organ-procurement practices—converged to shake public trust simultaneously.

The Times exposé precipitated the largest wave of organ-donor registry removals ever recorded. Verified data from the National Donate Life Registry show removals jumping from an average of 52 per day to 412 per day during the week of July 20 2025—a 700 percent increase. California alone recorded 841 removals on July 22 (its normal daily average was 36). Texas logged 6,420 removals for the month, compared with a typical 1,662; Tennessee experienced an 870 percent surge, and Colorado about 1,280 percent.

The Times reported that patients were sometimes still showing signs of life—gasping, crying, thrashing, or trying to remove tubes—while organ retrievals were underway. One New Mexico woman regained consciousness after family pleas to stop the procedure were ignored. The investigation suggested that federal pressure since 2020 to boost transplant numbers had eroded safety protocols, especially in “circulatory-death donation,” where patients are comatose but not brain-dead.

The timeline was swift. On July 20 2025 the Times story appeared; the next day, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy announced a sweeping overhaul of the transplant system after a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) probe found a “systemic disregard for the sanctity of life.” By July 22, California saw its record removal day, and a House oversight hearing convened. In late July, the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations (AOPO) accused the Times of “irresponsible reporting” that caused “immediate and catastrophic” consequences.

Alabama-specific data remain unavailable. The state uses the national Donate Life registry managed by Donate Life America, with registrations processed through Legacy of Hope, its designated procurement organization. Alabama did not release separate removal statistics and, notably, failed to report its 2023 donor-designation rate to Donate Life America.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department’s civil-rights lawsuit United States v. Alabama (Case No. 2:20-cv-01971, Northern District of Alabama) continues, with trial scheduled for April 2026 after repeated delays. Since the Department of Justice’s April 2 2019 findings letter, 1,045 people have died in Alabama prisons through the end of 2023—325 in 2023 alone, a record high for the second consecutive year. In 2019 the homicide rate was eight times the national average.

Federal investigators documented constitutionally inadequate protection from violence and sexual abuse, along with rampant excessive force. In one October 2019 incident at Donaldson Correctional Facility, a prisoner suffered multiple skull fractures and sixteen separate head and neck injuries. At Ventress Prison two months later, an officer shouted, “I am the reaper of death—now say my name!” while grinding a handcuffed man’s face into the floor.

The DOJ urged Alabama to create a centralized autopsy-report system for all inmate deaths. The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) never implemented it. Investigators later uncovered at least 30 deaths not disclosed to the DOJ, found only through autopsies performed by outside agencies. ADOC frequently classified homicides as “natural,” including one man who died of multiple stab wounds.

Alabama’s legal defenses have been costly: since 2020 the state has spent more than $57 million on lawsuits and settlements—$39.7 million on private lawyers fighting the DOJ and class actions, and over $17 million defending officers and paying claimants. Plans for a $1 billion new prison in Elmore County have been postponed until 2026.

In April 2025, Montgomery County Circuit Judge J. R. Gaines delivered a landmark ruling in eight consolidated lawsuits against the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and state corrections officials, denying motions to dismiss and holding that state immunity does not shield officials who act “willfully, maliciously, fraudulently, in bad faith, beyond their authority, or under a mistaken interpretation of the law.” The families had presented evidence that Alabama’s Uniform Anatomical Gift Act was violated and that a conspiracy to conceal the practice may have occurred. Judge Gaines also ruled that the statute of limitations could not bar claims if defendants had “fraudulently concealed the alleged crimes.”

A second judge, Jefferson County Circuit Judge Patrick Ballard, issued a similar ruling in the Matthew Harrell case, allowing claims of unlawful conversion, conspiracy, and wantonness to proceed. Families of at least eight deceased inmates allege that UAB’s Department of Pathology systematically removed and retained organs without family consent for medical training.

Examples are chilling. Jim William Kennedy Jr., 67, who died at Limestone Correctional Facility in 2023, was returned to his family “with only the eyes remaining.” Charles Edward Singleton’s body arrived decomposed and completely devoid of organs, including his brain. Kelvin Moore’s family drove four hours to UAB to collect what they were told were his organs in a sealed red bag—never sure what was actually inside.

Consent forms between ADOC and UAB were signed not by families but by wardens, each declaring the warden a “legally designated representative” with “no limitations.” Plaintiffs contend that only coroners, not prison officials, have such authority. Alabama’s 2021 law expressly prohibits medical examiners from retaining organs without next-of-kin consent. Attorney Lauren Faraino emphasized: “It was very, very clear—a medical examiner may not take an organ without family consent.”

Financial records illustrate motive. A 2017 UAB Division of Autopsy report showed that 23 percent of annual revenue (2006–2015) came from ADOC autopsies, 29 percent from the state’s Department of Forensic Sciences, and nearly half of total income from corrections-related work. ADOC paid $2,200 per autopsy and $100 per toxicology test.

In 2018 thirteen medical students discovered that roughly one-third of lung-pathology samples came from deceased inmates. Their 30-page internal report questioned the ethics of the practice, only to be told that prisoners’ organs offered “more dramatic pathology” because of inadequate healthcare—“It is easier to study a 3-centimeter tumor than a 3-millimeter one.” A UAB ethics committee deemed the practice “ethically permissible,” reasoning that organs “benefit future patients.” Following complaints, the university removed identifying labels that indicated incarcerated sources.

The system collapsed in April 2024, when UAB terminated its autopsy contract with ADOC. Since then, the state has been unable to find another vendor for autopsies in natural-death and overdose cases. Because Alabama law mandates autopsies only for deaths from “unlawful, suspicious, or unnatural causes,” many prisoner deaths now receive nothing beyond toxicology screening—leaving a massive investigative void in a prison system already documented for concealing violent deaths. Attorney Faraino estimates that more than 100 families may have been affected between 2006 and 2024, and she continues to hear from new ones weekly.

While Alabama reckons with those revelations, the Harvard Medical School body-trafficking prosecution closed another disturbing chapter in 2025. On May 21 former Harvard morgue manager Cedric Lodge pleaded guilty to interstate transport of stolen human remains before Chief U.S. District Judge Matthew W. Brann in Pennsylvania. Lodge, who faces up to 10 years in prison, admitted that from 2018 to 2020 he removed organs, brains, skin, hands, faces, dissected heads, and other parts from cadavers that had been legally donated for research and teaching, then sold them without consent.

His wife Denise managed sales and shipping, collecting $37,355 from one buyer, Joshua Taylor, whose PayPal notes included phrases like “$200 for braiiiiiins” and “head number 7.” Katrina Maclean, owner of “Kat’s Creepy Creations” in Peabody, Massachusetts, is the only defendant still fighting charges, arguing that human remains are not legally “goods”; her motion to dismiss was denied in July 2025. Lodge had allowed her to enter the morgue to select body parts, some of which she had tanned into leather. Other convicted collaborators include Taylor (Pennsylvania), Jeremy Pauley and Matthew Lampi (both Minnesota), and Andrew Ensanian (Pennsylvania).

Parallel thefts occurred elsewhere. Angelo Pereyra, a pathology assistant in Kansas, stole organs and fetuses from 2018 to 2022 and was sentenced to 18 months. Candace Chapman-Scott, of Arkansas Central Mortuary Services, stole remains—including two stillborn babies—from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and received 15 years, the longest sentence in the case.

The trail began with a tip to Pennsylvania police in June 2022, followed by a basement discovery of buckets of organs that July. Federal investigators widened the probe, and a grand jury indicted the Lodges and four others in June 2023. Harvard fired Cedric Lodge the previous month after nearly three decades of employment.

Harvard Medical School’s dean, George Q. Daley, condemned the acts as “an abhorrent betrayal.” An external review in December 2023 found “inadequate oversight” and insufficient documentation of retained specimens. The panel noted that the three-person morgue staff operated without supervision and that a main freezer suffered water damage for more than a year. Reforms now include surveillance cameras, barcode tracking, dual-witness packaging of bodies, and sealed containers before cremation. Yet none of Lodge’s supervisors were disciplined.

Civil litigation brought by 47 families was dismissed by a Suffolk County judge in February 2024, who ruled that Harvard had acted in “good faith” under Massachusetts law. Plaintiffs have appealed to the state’s Supreme Judicial Court, arguing that the university failed its duty of oversight. In the meantime, many donors’ families have withdrawn plans to give their bodies to Harvard. Attorney Jeffrey Catalano summed up the mood: “Many questions and concerns remain, which they hope to have the opportunity to discover and address.”

This investigation was conducted over a six-month period by the Anidjar & Levine Research and Policy Analysis Team between April and October 2025. It draws from verified court filings, government records, and over 150 primary and secondary sources, including Department of Justice reports, HRSA investigations, and data from the National Donate Life Registry. The findings were cross-checked against credible media outlets such as The New York Times, Newsweek, CNN, ABC News, and official state and federal databases. The investigation seeks to illuminate the emerging convergence of prison oversight failures, organ-donation ethics, and the breakdown of consent protections for incarcerated individuals in the United States.

To be continued…..